“Breathe, Breathe in the air,

Don’t be afraid to care.”

Pink Floyd

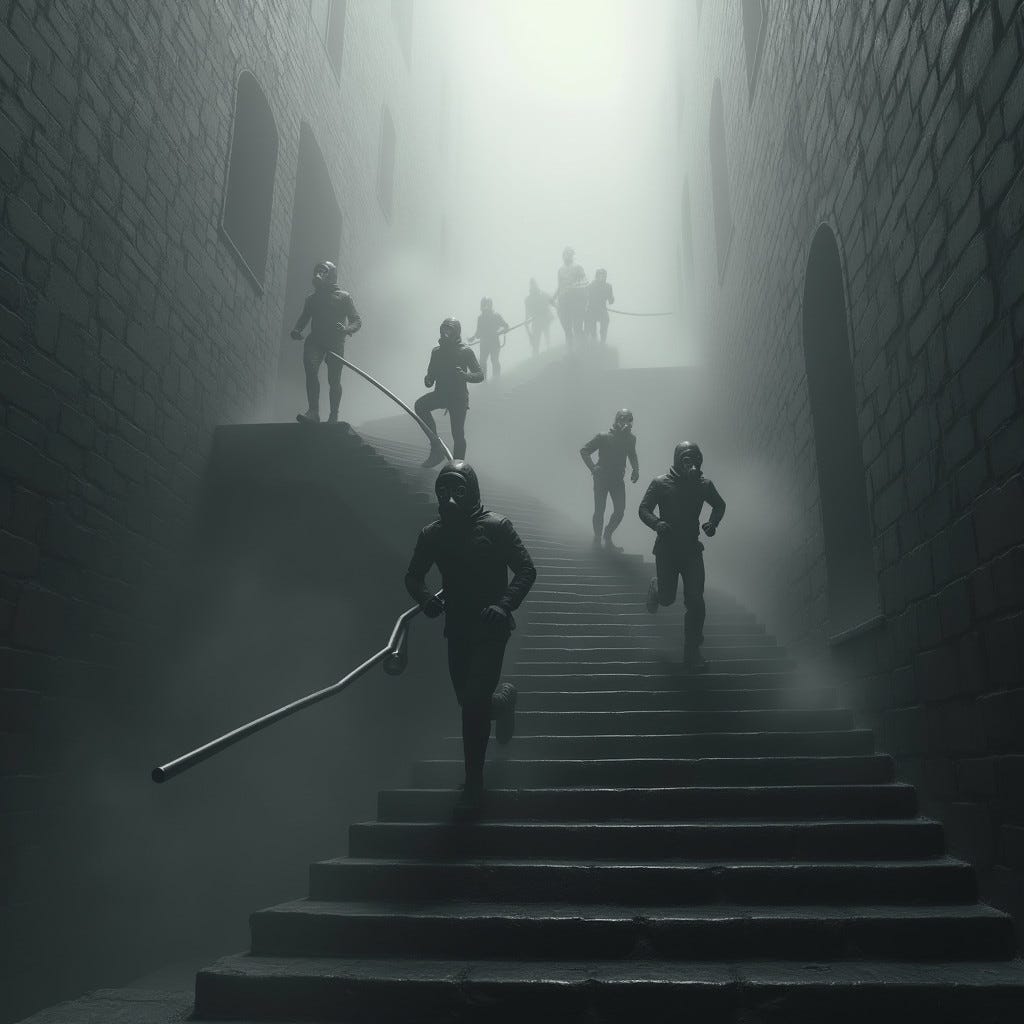

Down with AQI - generated with Nightcafe

Slouched in my couch, I was in my default posture for Zoom pitches.

From the other end of the ether pipe, Manoj leaned eagerly into my screen:

“Sir, basis our consumer interviews, runners don’t put in the hours on machines. After Diwali, when they get off the streets, their weekly mileage drops drastically. On average, the people we interviewed put on 6 kilograms before they begin running again in February.”

I felt my left eyebrow twitch. Manoj signalled Rajat to scroll to the next slide.

“Sir, we’ve been checking the number of runners at Nehru Park every weekend for the last year and half. See how sharply the green line drops.”

“And this red line?”, I was having difficulty adapting to my new varifocals.

“That’s the AQI, Sir. We can see inverse correlation between AQI level and number of runners at Nehru Park.”

Rajat joined in - “We think the drop will be the same at other locations across Delhi/NCR.”

I abhor lazy assumptions like that one. But the boys had it right. October is a cruel month in Delhi. It begins with the prospect of cooler days after the stifling humidity of the monsoons, with the promise of Diwali sweets and gatherings of the clans, but descends into the acrid air of thermal inversion, stubble burning and firecrackers. By late-October, when I awake in the dark, instead of grabbing a banana before I lace up my shoes, I slump into my couch and doomscroll the AQI readings. The best I can hope for is a narrow window in the afternoon, when the AQI flags fade from maroon to amber, and I dare to take a short trot in the neighbourhood park. By Diwali, even that prospect goes up in smoke.

“Yeah, probably. But what’s the idea?”

“Sir, our idea is called Marble Temple Run.”

I inched up in my couch. “Sir, This is an asset-light model for indoor running.”

I closed the stock-market tab on my laptop, and allowed the call to fill my screen. Manoj and Rajat shared a floor plan for Elect Mall. Four floors, each with a plate of about twenty thousand square meters.

“Sir, we walked a circuit - this dotted line in blue, and mapped it on Strava. Two point five kilometers, plus an altitude gain of twenty meters.”

“Using the escalators?”

“No Sir, we used the backstairs, but before 10 a.m., the escalators are not turned on.”

On my screen, I could see my own head tilted in interest, I was scratching the side of my neck, always a giveaway, and my forehead was wrinkled in absorption.

“But the AQI is not much lower indoors; in the morning, when I turn on the air purifier in my living room…”

“Right, Sir. But this is why we need to raise funding. If you install HEPA filters in the Air Handling Units, you can get the 2.5 PM down to 50.”

I was in. The mandatory slides with financial projections slid by; they never meant anything, but the idea was bold, and spoke to my own winter frustrations.

“Let me get back to you”, I shut the lid on my laptop, and Whatsapped Angad.

Angad had dropped out of school at fourteen to build robots, gone to Georgia Tech on a full scholarship, and was now building filterless air-cleaning systems for large industrial projects. I’d made a small investment in his start-up, and engaged with him occasionally.

I found his reply when I woke the next morning:

“HEPA filters are not a solution - there are many openings for people and dust to come in. Also, the HEPA filters induce backflow as they get choked, increasing energy consumption in real time, and also damaging the AC.”

“That’s a good start”, I texted back, then forwarded his message to Manoj, telling him to get in touch with Angad.

This is going to be quite an exercise, Angad called a few days later.

Exercise is good, I replied, and offered to pay for a trip to Delhi, to monitor airflows and pollution levels inside the mall. We need to complete all our modelling before the winter is over, I reminded him.

I worried about how much we could accomplish in stealth mode. At some point in time, we would have to get a large mall-owner on board. But maybe that could wait, till we got a handle on the technical dimensions of the project. For Angad’s first trip, we mobilised a squad of some fifty runners, disguised in kurta-pyjamas, frilly skirts, tank-tops, biker-black leather, co-ord sets, even a couple of business suits thrown in for good measure - each runner armed with an air quality monitor, synched to their smartphones.

Angad had walked the mall with Rohit and Manoj the previous night. I peered over the handrails of the third floor food court, fantasised about an optional loop up and through the carpeted aisles of the multiplex, and wondered whether we would need hydration stations for an indoor run.

Across my dining table, the air-purifiers humming away as the smog settled over a sleeping city, Angad generated a CAD approximation of the mall on his laptop. Ten ground-level entrances, he pointed out on his sketch. Two entrances to staircases on each floor. Every elevator door. Exhaust hoods where dosas sizzled. We were going to need every one of those fifty volunteers.

I consumed too many calories that day - lurking near ice-cream counters, grabbing a gazpacho soup and apple pie at the Urban Green Cafe, sharing a massive brown bag of fries with Angad and Manoj. Rajat was installed in a co-working space across from the parking lot, along with Angad’s CTO, looking at updates from a sample set of five volunteer phones, messaging us where they were seeing data gaps, or puzzling inconsistencies. I had asked Santosh to join us from Bangalore, and oversee volunteer deployment. His eyes were everywhere, his bulk unmoving, his gentle voice over the phones soothing, on our day of a million steps.

“Over a million, actually”, Angad recorded, one of the more trivial of data points he recorded. Over the next two weeks, I observed the journey of AQI data points from monitors to phones, migrated over the net to Angad’s servers in Mumbai, joining and mutating into a virtual map of dust clouds.

“Dust is not that dangerous”, a pulmonologist had reminded me. “Particles of 2.5 microns are one-tenth as fine as human hair, and our airways have no way of filtering them out.” Dr. Mansingh interrupted himself to take a call, and I chuckled at the notice under the glass on his desk: “Patients who suggest treatments found on Google will be charged double.”

He turned back to me, a little puzzled by my smile, “These fine particles line the lungs and, over time, reduce effective lung capacity.”

It wasn’t going to be easy to tackle PM 2.5 in a space like this, Angad cautioned as he tried to corral the data. ‘Airtight’ is only an approximation, and fails when confronted with an assault of ultrafine particles. We’d need scores of his MK II machines up and down the marble passages of the mall, air curtains at every entry point, draft excluders of high-performance silicone.

“And I don’t know what we’re going to do to keep out the assault of exhaust gases from the basement parking”, one of Angad’s e-mails linked to a CG visualisation of the elevator shafts, which were rendered in a dark cloud of 1000+ AQI. The deployment plan, when he finally generated it, was staggering. The Marble Temple Run was nothing like a computer game - it was going to take real money, lots of it; lots of persuasion, and a huge leap of faith.

“Boss, even let’s assume the technology works”, Ashvin never wasted time in getting to the point. “I think this project will take at least ten years to pay off. My investors will ask me, what if the government manages to fix air quality by then?”

Not happening, I assured him. We’ve been coughing since the late nineties. The CNG buses bought us a few years, but twenty five years later, we’re worse off than we ever were. I quoted my friend and policy maven Shruti Rajagopalan to him,

“It takes decades, maybe centuries to develop high state capacity that can tackle commons problems, mitigate pollution and create a world-class clean public transportation system.”

“This I believe”, Ashvin looked at me intently through the thick lenses of his black-framed glasses. “I’m with you.”

A few days later, Ashvin called. “Boss, I don’t know about Elect Mall, but we have this commercial complex in Greater Kailash…”

“Archana! I’d forgotten!”

“If nothing else works, we can try it there.”

Once an iconic building in South Delhi, Ashvin’s family property had been home to an upmarket cinema, a celebrated TV channel, even a boutique owned by a friend. I hadn’t been there in years. It was one-tenth the size of the site we had planned, and marble wasn’t the default flooring when it was built. But we would probably be able to raise the funds required from family and friends, and save ourselves the gargantuan effort of peddling our fantasy to mall-owners and their interior designers.

“Marble Temple Run is not going to happen”, I got Manoj and Rajat onto a Zoom call that afternoon. “We need a new name.” I told them of Ashvin’s offer. I think Angad was also relieved - the scale of the project was much more manageable. Ashvin probed to be a rock-star, and brought us into discussions with his team of architects and designers, as they planned their first renovation in fifty years.

“Instead of marble, can we do matt-grey stone for the passages?” I asked at one meeting. “Less slippery…”

“That might go with our minimalist intent”, Saurabh reflected, “otherwise all malls look the same.”

One Sunday, as the spring breezes had begun to clean the air of Delhi, we brought a group of runners into the Archana complex.

“Solid workout this will be” Mo Oberoi said, star of a score of ultra-marathons. “More up and down, than in and around.”

“50 AQI, really?” Annie asked.

Angad had sent me a new set of working documents, with a target of sub 25 AQI. Yes, I nodded, confident.

“Test run the day after Diwali”, Ashvin set his team a target.

“Real torture test!”, I was completely enthused.

As was Delhi’s running community, when we began to talk about our plans:

Up With Running, Down With AQI.

“Great name, Babajee!” Mo applauded.

“I got that from you, Mo, when you said the course was more up and down, than in and around!”

We got Adil Nargolwala to plan the inaugural race. “Each circuit is less than a kilometer”, he looked at his Strava readout, “with a 35 meter climb. A five kilometer event will mean 175 meters of climbing. Good workout for the lungs.”

“And 175 meters of descent. Not for these old knees…” I said, more to myself.

With such a tight loop, we realised, stronger runners were going to be lapping others. Should we go full race-mode, and issue chips, to track the number of laps? This was getting way too complex, we finally agreed. Let’s do this on an honour system, and not have any prizes. Between Adil and Mo, we decided to keep it simple. Set a cut-off time of forty five minutes for each batch of runners, and shut the entry ramp at forty minutes past the hour. Send in a new batch every hour. Hundred runners per group, max.

“We need the space cleared by 10 a.m.” Ashvin had decided. “So we can clean up, and open the Mall at noon. The day after Diwali, there’ll be no traffic till lunchtime, in any case.”

Let’s begin at 4 a.m. - we got greedy. Five batches of a hundred runners each. Diwali 2025 was on October 21st, and we pushed the entry forms out on Instagram at 00:01 on October 1st. By the time we woke up, there were over five thousand forms filled out. It would have been a simple matter to tag ‘First Come, First Served’ onto our site, and to reject any entries after No. 501. But we hadn’t even considered this kind of response. The tech volunteers located the time stamps on the applications, sent acknowledgements to the first five hundred, while we drafted an apology to all those who had got off to a late start.

“But the course will be open to runners for designated hours through the winter. Please wait while we formulate these plans”.

“I might as well not sleep,” I grumbled to myself, as I played the last hand of teen-patti, Sanjoy’s dining table strewn with the detritus of a long Diwali party. Cut-glass tumblers with dregs of whisky, toothpicks from bite-sized kebabs, wrappers from pralines, packs of cards discarded because a player declared they were unlucky.

In the dense smog of AQI 999+, the occasional rocket still streaking the night sky, the street lights of the Gurgaon Expressway created a tunnel through which I drove to Delhi. I had time to shed my silk kurta for runner’s shorts, even if I was only going to spectate, remembering to pick up my AQI monitor as I exited home.

It was not quite 3 a.m. when I drove into the Archana parking lot. Arc lights illuminated the main entrance, and flex banners declared the event. Volunteers were already in place to check entry badges, and from inside the foyer, Angad was beaming as I passed under the whoosh of the air curtains.

“15 - and our simulations think it won’t climb above 22 at peak runner load.”

We walked the course, spiralling all the way up to the 5th floor, then swooping back to the ground level, individual meters scanning the air quality.

“Looking good, really good!” I clasped Angad’s shoulder.

By 3:15, the first runners began walking down from the BRT corridor, on which the traffic police had permitted car-parking on the eastern side, all the way from Moolchand to the Chirag Delhi crossing. For a hundred runners at a time, that was very generous, we thanked ACP Traffic, Rajpal Yadav, for his cooperation. By 3:45 a.m., ninety nine runners had logged in, and at 4:00 a.m. sharp, Adil flagged them off.

“4 is too early - I’ll do the 6 a.m. batch, Boss!” Ashvin had promised.

“On my way”, he texted at about 5:30, when the first few runners from the second batch had just emerged into the smoggy dawn. The parking lot was now crowding, runners from the first batch, sipping recovery drinks; spouses of runners, whom they could spot through the plate glass of the foyer, every time they turned for the next loop; early arrivals for the third batch; and growing by the minute, disappointed runners who had been late to register in the wee hours of October 1st. Dwarka Runners, one lot of T-shirts read. Members of the Jat Squad pointed to a window on the fourth floor, through which you could glimpse some bobbing heads. “Agley Sunday karengey - pakka!”

“Stuck in traffic”, Ashvin texted at 5:45. I checked with the registration desk - only forty two runners had shown up for the 6 a.m. batch. We sent volunteers out on motorcycles to survey the scene.

“BRT clogged”, one sent a voice-mail.

“Parking under LSR flyover jammed”, another.

“Told my driver to go home”, Ashvin texted, “Jogging there.”

Ten minutes later, ACP Yadav* arrived, in a flurry of flashing lights and annoyance. “Yeh kyaa haal banaa rakha hai, aap logon ne? Bola tha, sau-sau runner hi hongey. Def Col se le ke Khanpur tak sadak band kar di, aap ke tamasha ne!”

Ashvin jogged into the car park. “Kaise, ACP saab!”.

I filled him in. “Deep shit, Boss!” he looked at me.

It was now past 6. The neon colours of departing runners sparkled in the flashing lights. Some stopped to rubber-neck; wardens urged them to leave. The third batch looked at their smart watches - it was way past starting time. Volunteers at the desk stood up and looked at us for guidance. We looked at Yadav.

“Janta sochti hai, sarkar ka chutiyaa bana sakti hai. Hum nahin honey dengey!”

“Chootiye to hum hain”, Ashvin muttered as he took me aside. “Ordinary people like you and me can’t do a fuck, when our government doesn’t care about our health.”

Loose translation of DCP Yadav’s anger:

“A right royal mess, you’ve gone and made. You said there’d only be a hundred runners at a time. From Defence Colony to Khanpur, your tamaasha has clogged the roads.”

“You think you can fuck with us? No way, buddy!”

Ok. This was a fantastic read. Fact or Fiction 😀