Ganga III

The Lap of Her Swell

“I’m feeling very pukey”, Ilya said to me that evening in August 1996.

“We’ve all had the loosies”, Sushil and Oona echoed the state of their insides.

“Monsoon bellies”, Kalyan observed, rolling another cigarette.

The next morning, piles of clouds were heaped above the ridges that faded into a haze of ultraviolet. The grass needed cutting. Hubert’s charts waited for Oona and Sushil. We had another coffee, then Bacchi Ram brought word that we should begin our workshop -

“Doctor Sa’ab, Oona, Ilya - sab ki tabiyat dheeli hai”.

We broke for coffee at eleven, and Anita said she would go over to check on how they were.

“Not good”, she reported.

“I think they need medical attention”.

Little Ilya, still going on four, my littlest friend, was comatose.

Oona, strider of hills and dales, and the most fearless swimmer I knew, had to be supported to get down the hill.

Sushil was woozy, but had his wits around him.

“This may be the mushrooms we ate that evening”.

I flashed back to an evening that summer, when we were all visiting my parents in Ranikhet, two hours away. Ma took one look at Sushil and Oona and pronounced that they were not looking well at all. I hadn’t noticed.

“Some mushrooms we ate, Aunty, didn’t agree with us.”

“You must not eat wild mushrooms. Please promise me you will never have wild mushrooms again”.

“We’ll think about it”.

Sushil and Oona had received a grant to identify the edible mushrooms in the forest around our home, and I knew they would not be persuaded to abandon their research. Sushil had equipped himself with reference works on fungi, and a microscope for which he would prepare slides of mushrooms from their foraging. Every new specimen would be examined and compared with the literature. If the fresh samples appeared to be edible, he would eat a tiny sliver, and observe his body’s reaction for twenty-four hours, before declaring it kosher.

That week in August, Sushil’s mushroom protocol broke down. Oona had been to Nainital on work, he to Lucknow, and when they returned to Satoli, Oona made a salad with the mushrooms in the fridge, and pronounced it delicious. Ilya had a precocious fondness for mushrooms, and by the time she brought the plate over to Sushil, there were only slim pickings for him.

“I think one of those mushrooms may have been a Destroying Angel”: Sushil had been reviewing his notes.

For the first twenty four hours after amanita mushrooms are consumed, the symptoms are not alarming - the nausea or indigestion that would accompany a routine case of food poisoning. But all this while, the hepatotoxins are working their way into the victim’s tissues, and beginning to destroy her kidneys and liver.

“As little as half a mushroom cap can be fatal if the victim is not treated quickly enough.”*

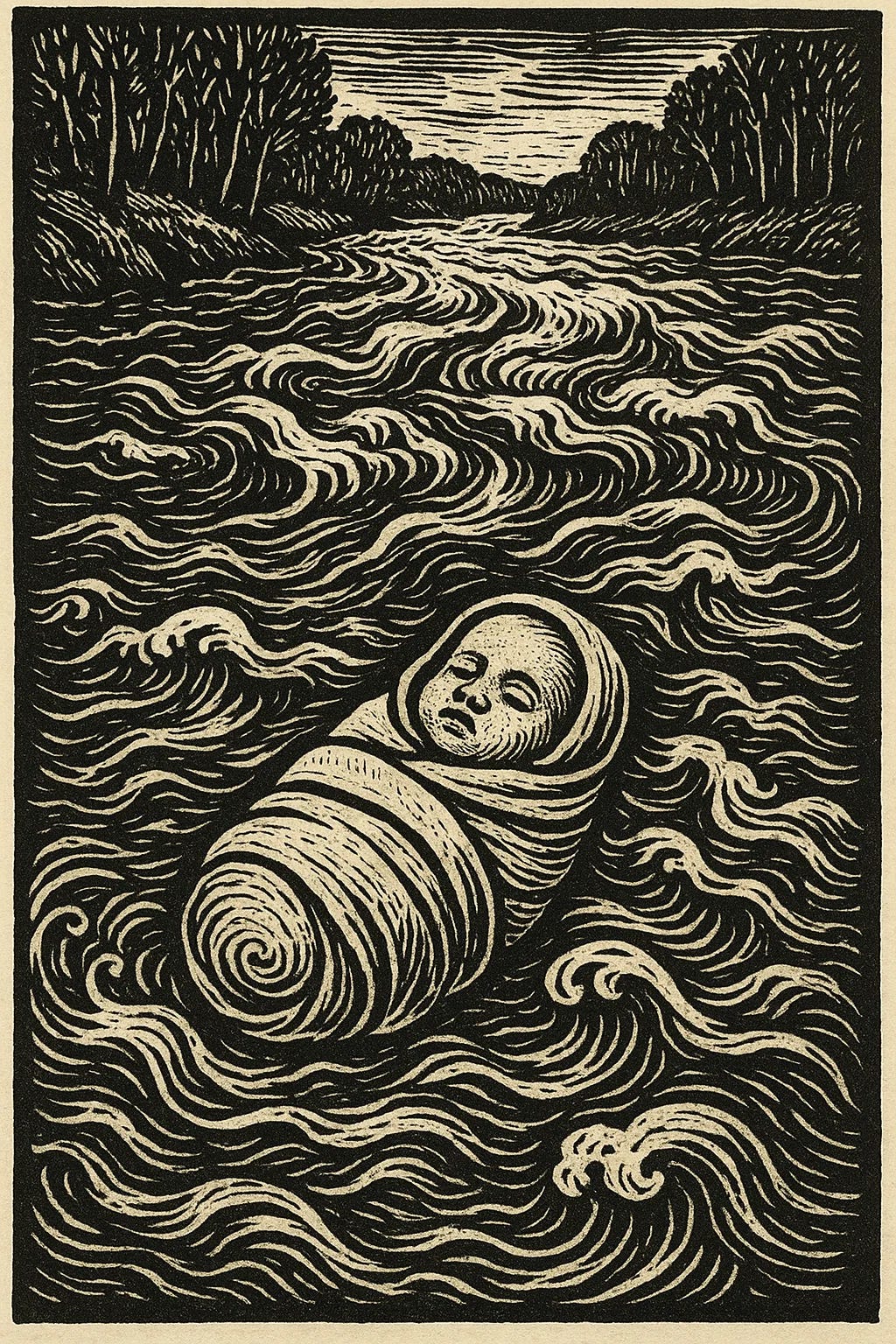

Ilya and Oona were admitted to the Military Hospital in Ranikhet about forty-eight hours after they had eaten the mushroom salad. Nowhere near quickly enough - the window for treatment of amanita mushrooms does not extend beyond twenty four hours. By next morning, Ilya was a lifeless bundle in her father’s arms, and Oona delirious as we strapped her into the front seat of Kalyan’s car to drive down into the plains.

We stopped on the far side of the bridge over the Ganga at Garhmukteshwar. In a black Ambassador with army plates, Ilya’s Naani and Naana waited for us. There was nothing to be said. Gurbir’s proud, handsome face was reduced to a mask of dread, and he waited near the car with Oona.

Jasjit led us down to the ghats, her torch on the ready for the night that was descending. A boatman rowed us into the swollen river. Jasjit handed out texts for each of us to read aloud, and I helped Sushil cast his child’s little body onto the swollen waters of the Ganga.

Ilya, child of mountain breezes, now merging into the eternal cycle of river and sea.

For the next seven days, the doctors at Batra Hospital fought wave after wave of ravaging toxins, but Oona’s body could not be saved. I was to be engaged in Bangalore two days later, but we drove up to the hills she so loved, with Oona’s remains. In the glistening jewel of Panna Lake, where she had so often matched me, stroke for stroke, Gurbir and Sushil allowed her ashes to settle, to find their rest beneath the trees and the clouds, beneath the silver stars of mountain nights.

When I returned north, officially affianced, Sushil had taken himself to the Sivananda Ashram in Rishikesh. Come and spend a few days with me, he had left a message. I missed my train and caught an overnight bus instead, aslope in my seat, the journey a jerky sensorial succession - a shadowy tea stall, giant potholes through which creaking shock absorbers lurched, passengers alighting and fading into dark fields. Hot milk foaming in kulhads at the bus station at dawn, lurid jalebis under fluorescent lights. The ashram, where I joined Sushil and Ajit for breakfast, a long line of thaalis in a darkened hall.

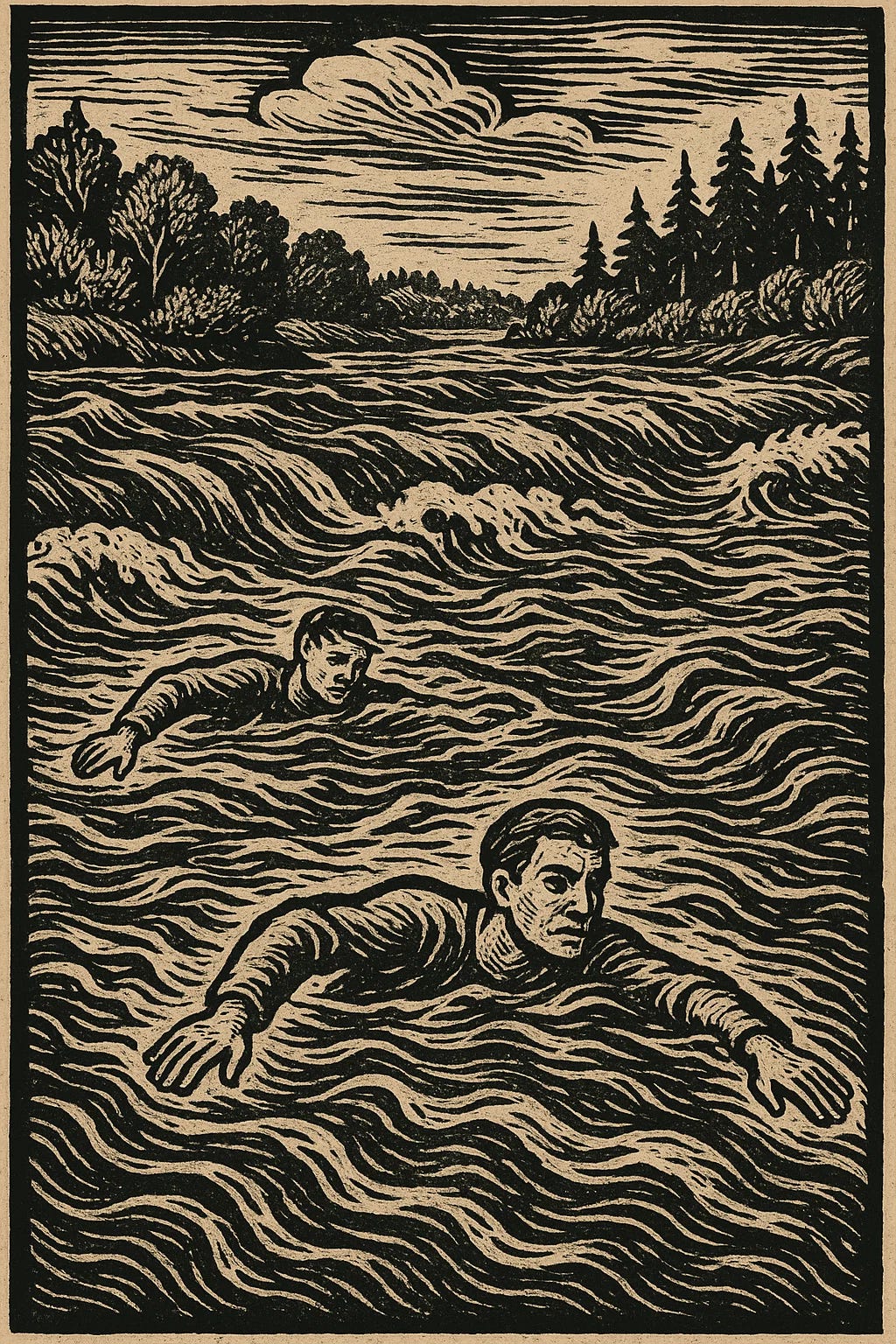

Ajit reclined on the beach below the Parmarth ashram, while we took a dip in the Ganga. Not today, I had told Sushil when he asked whether we could try swimming the river, my brains too fried from the ride. Back on the shore, the sand was soft, the September sun comforting. By noon, I was restored, and when Sushil glanced at me, we knew this was the time.

I stroked into deeper waters, Sushil at my shoulder. The river ran high, but not fast. At first. The closer we got to mid-stream, the more we had to yield to the river’s volition, to its monsoon-fuelled urge to reach the sea. Keep stroking, I told myself, keep aiming for the far shore. Now we were being pushed back by the deep bend of the river, as it raced toward the Sivananda Jhoola. Keep your head down, keep stroking. If you keep your head down long enough, the next time you look up, you will be closer to the shore. Just that little mite closer. No, it’s not an illusion, this is the physics of force and motion.

The next time I looked up, we were speeding under the suspension bridge. Some people had spotted us, and set up a loud cheer. We looked up long enough to wave back, long enough to look downstream, to where rocky rapids threatened. Hard right, we gestured to each other. The wall of water rebounding from the riverbend eased into the broadening stream, the current slowed, the adrenalin eased, and we stroked for the far shore. Grasped at the slippery steps of an ashram, and pulled ourselves up by our fingernails.

Onto a marble courtyard, where we looked at each other’s jocks, and giggled. We hadn’t thought this through. We were almost one land mile away from Ajit and our clothes. One land mile that took us onto the highway, then down into the bazaar. Past a group who recognised us as the swimmers they had cheered. Over the bridge from which they had cheered. Down onto the left bank of the Ganga, past the Parmarth Ashram, striding onto the sands where Ajit was snoozing.

Self-consciousness gone, lost to the Ganga, to which we had - for one joyous hour - so totally committed ourselves.

Give us a fag, Ajit Pappe, we commanded.