If Bihar Were A Nation, If Beale Street Could Talk

If Bihar Were a Nation

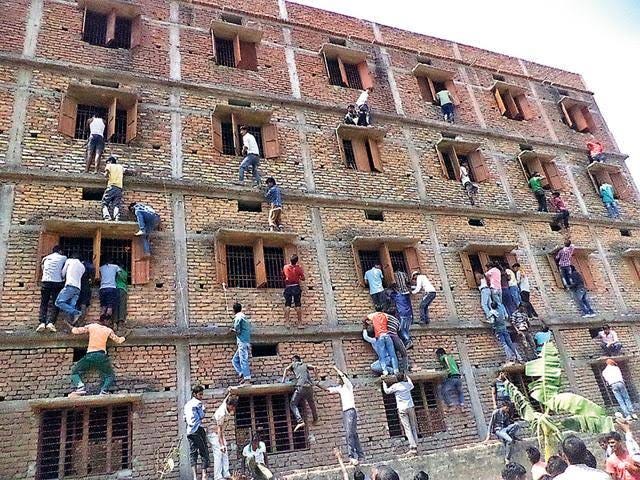

An Exam in Bihar

If Bihar were a country, it would be the largest of the world’s poorest nations.

I define ‘poorest’ as countries with an annual per capita income of less than 1000 dollars per year. Fifteen of these countries are in Africa, and the four poorest Asian nations are war-torn Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan, and the North Korean redoubt of Kim-il-Sung. The largest of these nations is Afghanistan, with a population of about forty million.

Bihar is ravaged neither by war, nor by a third-generation dictator. It sits in the heart of the Gangetic plain, and till Jharkhand was separated out, had huge mineral resources. Yet, its per capita income, of 640 dollars a year, is less than one-third of the average Indian, and less than one-tenth that of Goa, whose residents make over per capita GDP 7000 dollars a year, on par with Thailand.

The ten-fold gap between two states in the same nation is extraordinary. In the US, for example, residents of New York state and Massachusetts have per capita incomes of 76,000 dollars, while Mississippi comes in at 35,000, a factor of only 2.2.

One would have thought that, over time, incomes in different Indian states would tend to equalise - labour would move to places where incomes are higher, and employers move to places where wages are lower. Life, of course, is much more complex than economic models, and internal movements of both labour and enterprise are motivated by a great deal more than wage levels.

The major constraint, of course, is that there are simply not enough permanent jobs in India. Bihar is a major source of migratory labour, but the migration tends to be circular in nature. Most employment, whether in agriculture or construction, is temporary and uncertain. Wage levels are not high enough to support city rents and living costs of an entire family, so the village home and land - if any - remain the anchor, and most households don’t make a permanent shift to areas of higher incomes.

Returning after 45 years to Palamau, now in Jharkhand, economist Sudipto Mundle* noted “a complete transformation of the physical infrastructure” thanks to decades of government-led development. Whether in Jharkhand or Bihar, roads, electricity, and cell phones have connected our most remote villages to the world. Starvation has largely vanished, due to food made available by the Public Distribution System (PDS). The MNREGA scheme generates some income through public works programs, but despite all these measures, over 40% of Bihar’s children are stunted, and over half its residents are poor by NITI Ayog’s multi-dimensional poverty index. Public Education - after a fashion - is available to most Indian villagers, and enrolment at the elementary level is almost universal. There has been enough written about the poor learning outcomes of Indian schools, but it is a moot point whether this really matters when even those with advanced degrees find no jobs.

Formal sector jobs in India are heavily clustered - think Delhi/NCR, Mumbai, Pune, Hyderabad, Bangalore and Tamil Nadu. Each of these clusters generates synergies, both in skills, and between enterprises which develop buyer-seller relationships that sustain business activity. North of Mumbai, and east of Delhi - the bulk of the Indo-Gangetic plain - we have yet to see the seeds of any such clusters which could add substantial value in either industry or the services sector.

The state of physical infrastructure in Bihar has been a major obstacle to the development of business in the state, but - as Sudipto suggests - this gap is gradually reducing. However, law and order in Bihar has a poor reputation, and this doesn’t help with investment*. This April, we learned that is possible to steal a 500 ton bridge*** in the state, which lead to a hilarious riff on a popular Hindi song:

“Chura liya hai tumne jo pul ko, nahar nahi churana sanam”

(You have stolen a bridge, leave our canal alone).

Levity apart, in a nation as vast as India, it is quite easy for a state to fall off the map of potential places to invest and work in, and Bihar is deep in the shade. It is going to take an enormous amount of change to make this happen. I don’t have the faintest clue of how these changes will come about, of how equipped the state and national governments are to effect these changes, and, most importantly, of how the average Bihari regards her place in the Indian economy.

But I intend to begin finding out. In the second week of December, I plan to spend a little over a week traveling in Bihar, to get a sense of what keeps one hundred and twenty million Indians so far behind the rest of the nation. I am not an economic researcher, I am not a journalist, so I don’t have hopes for any deep insights.

Yet, at some visceral level of solidarity and fraternity, I feel positively offended that - a quarter of the way into the 21st century - this Indian state-as-large-as-a-nation generates incomes at the level of sub-Saharan Africa. And for reasons I can’t fathom, I feel the need to try understanding why.

***https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/how-a-60-ft-iron-bridge-was-stolen-in-bihar/article65389045.ece

If Beale Street Could Talk

The social drought of COVID turned me into a movie addict, after decades of relative abstinence. Sometimes the search for quality viewing became tiresome, and I would become indiscriminate, but often I lucked on high quality cinema. Some of the most moving films I saw during this period were about the long struggle of the black community in the US, hard-hitting, often angry cinema, hewing close to reality - though the series Underground Railroad, an intensely moving experience, was partly allegory, partly fantasy.

In no particular order, I list

The Trial of the Chicago 7, and Marshall, which deal with the distortions of the legal system;

MudBound, and Twelve Years a Slave, which I found both claustrophobic and compelling in the violence they depicted;

BlackKlansman, about a black cop infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan;

Judas and the Black Messiah, about the betrayal of a Black Panther leader;

One Night in Miami, a speculative account of a meeting between Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali and two other black leaders, Jim Brown, and Sam Cooke; and

The tight and idiosyncratic Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, with the entire action spanning just one recording session.

You could put it down to the phenomenon of recency, but a film I watched just last week was the most moving of all the black films I’ve seen in the last couple of years. Like many of those above, If Beale Street Could Talk is a true tale of the miscarriage of justice, of a young black man framed for rape by a vindictive policeman. But director Blake Jenkins - who also made the Oscar triumph Moonlight - crafted it as a romantic story of exquisite tenderness, of the slow blossoming of a lifelong friendship, of the promise of love throttled by venality, of longing and dedication, of the support of family, and finally of the hope that our children will live to see a better day.

You see your reflection in the art you witness. After watching Beale Street, for several days I was cast as a romantic, moved by the social and political tragedies of generations reflected in a single tear, in embraces that should have been, but never were.

Thanks, Alan.

I will look for the book.

True! Hadn't thought of that.