Tax Scissors Cut Deeper

On July 23rd, our Finance Minister hiked the tax burden on Indian households, by raising taxes on gains from selling assets. The shift in the tax burden, from companies to households, began with the massive cut in corporate taxes in 2019, about which I wrote* three weeks ago:

In 2014, income taxes collected from households accounted for 2.1% of GDP. Last year, they accounted for 3%. In the same period, corporate tax collections dropped from 3.4% to 2.1%. An almost exact inversion.

Many economic commentators have written about this gradual shift, but in the last week of June, it was as if a dam of resentment against the government broke. Anger, criticism, sarcasm and wit flooded social media. Coming on the back of leaking airports and exam papers, flooded cities, and rail accidents, the broad tenor of the twittering classes was - We pay taxes like the US, but get services like Gambia.

There is a strong ring of truth to this sentiment - even as I draft this, word comes in that at least two young women died when a basement coaching center in Delhi was flooded by rain water. Ironically, the center coached those preparing to become civil servants, the very class of people who are supposed to ensure basements are not misused, that drains are cleaned on time, and, if we get lucky, Delhi’s master drainage plan*, last prepared in 1976, gets updated.

Two tax changes, in particular, provoked a strong reaction from the investing, and twittering, classes - the hike in capital gains taxes on equities, and the removal of the ‘indexation’ benefit on the sale of property, which gave partial relief from taxes on the appreciation of property prices. There was a sound logic behind this indexation - when property prices move up, with inflation, there is no substantive change in the value of the asset. A 3-bedroom house left to you by your parents is still a 3-bedroom house - why pay tax on its enhanced price?

One friend commented, “after fuelling inflation, the government will tax you on it.”

There is a great deal of depth to this terse observation, as one of the main reasons for inflation is the government’s perennial need for cash, and the central bank’s willingness to create conditions for government borrowing. After the pandemic, this dynamic deepened, and the government borrowed even more money, trying to push the economy into recovery, as the corporate sector was not investing in the future.

Public investment in infrastructure came to the fore, but public anger aside, there is a central economic issue about bad quality construction - if airports shut down because roofs collapse, or if bridges are washed to the sea, what happens to the expected return on investment?

OK, that’s a rhetorical question, because we all know that the return drops, but does it drop below the point where that investment was justified? This we will never know, because governments are not exactly forthcoming with such analyses. Besides, they can always hide behind righteous statements about the public good not always translating to rupees and paisa. What we do know is that the government is running out of investment steam. Ajay Seth, Economic Affairs Secretary, said as much. With the Centre facing competing demands on fiscal consolidation and priority revenue expenditures for central sector schemes,

GoI has reached a level where it (spending on infrastructure) is the maximum it can sustain.The ball for fuelling growth has been handed back to the private sector. Which, judging by its capex plans, it doesn’t intend to chase hard. If anything, private sector activity is slowing. Another Secretary to the government said* there has been a ‘modest’ reduction in the projections for corporate profits, and hence taxes.

The projection incorporates the decline in corporate profits of the top 170 companies for the first quarter (April-June) of FY25, excluding banks and the financial sector.

Including these sectors, there is an approximate increase of 4 per cent. This number is way below earlier assumptions of a growth in corporate profits of the order of 10% per year, and leads to a situation where:

India Inc is not fuelling growth, despite lower taxes

Government is running out of fuel, so

Let’s raise taxes on households.

But - someone seemed to have reminded the government in the final hours before the budget date - households are also suffering because of an employment crisis. Oh, that! Hmm, let’s cobble together a plan for internship. Except it isn’t exactly a plan that stands up to scrutiny, as social media was swift to expose. This tweet, by Swati Vaidya, sets out the facts:

Top 500 companies have about 73 lakh (7.3 million) employees as of now.

That means an average of 14600 employees in each of the 500 companies, are working in these companies currently.

1 crore internships in 5 years in 500 companies will mean 20000 internships in 5 years, which is about 4000 internships in each company for each of the 5 years.

So a company which employs 14600 people is supposed to provide internships to 4000 persons in a year. Which is little over 27% of the current total number of employees.

Can a company continue to remain in the top 500, by having such a large portion of its workforce as 'interns'?

For this, center has allotted Rs. 2 lakh crores. Companies are to bear the cost of training the interns by spending their funds allotted for the CSR.

If only job creation was as easy as this empty sloganeering. So true. Whether investments or hiring, corporates respond to market conditions. When the demand for IT exports was booming, Infosys set up the Infosys University, to ensure a steady funnel of trained coders. The experience of ITIs, or Industrial Training Institutes, echoes this reality - when they are situated close to booming clusters, like automotive factories near Pune, both the quality of training, and placement rates, are decent. But, on aggregate, fewer than 1% of ITI graduates* get jobs.

Indian households suffer from low incomes, low aggregate demand, and a low supply of quality jobs. The latest budget shows no signs that our economic policy planners have a route map to a better place.

While they’re figuring it out, grin and pay more for your capital gains.

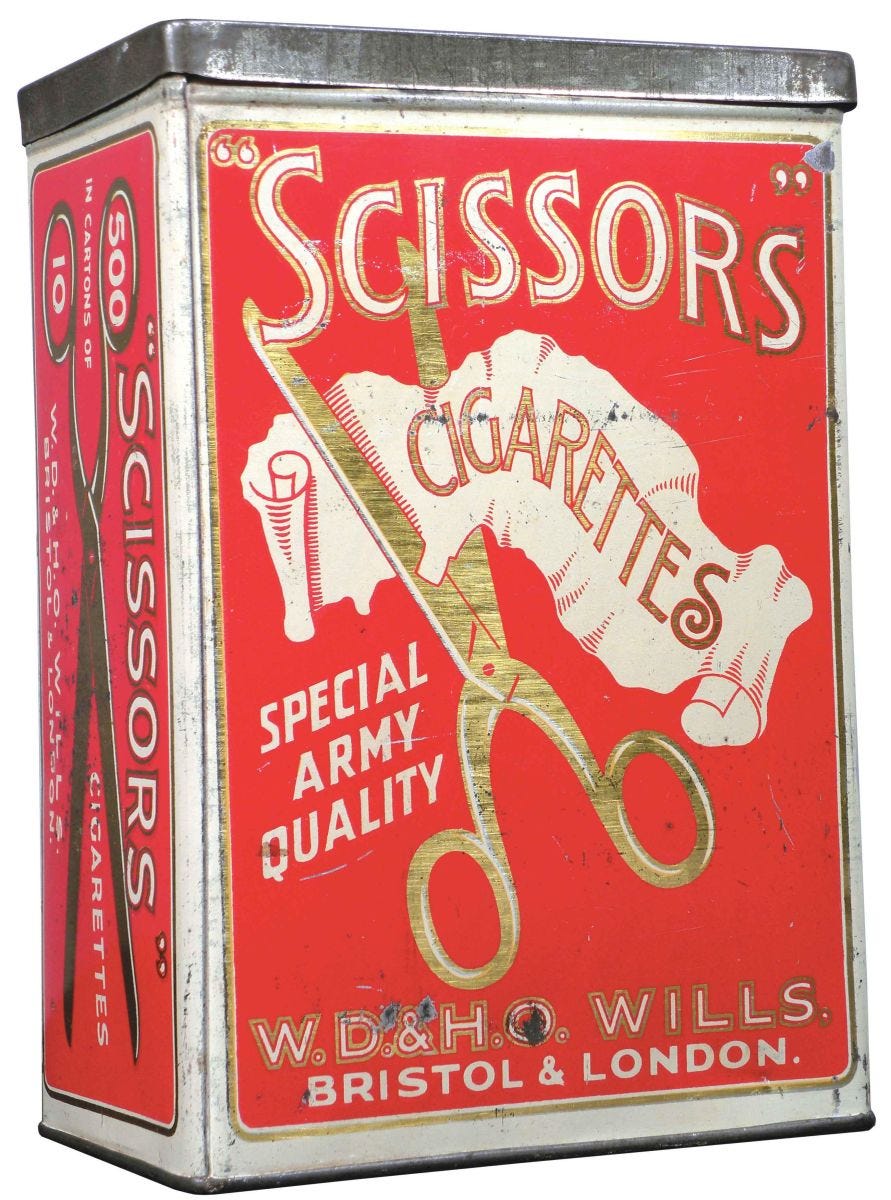

The scissors of taxes fuel corporate profits: https://mohitsatyanand.substack.com/p/a-new-story-for-growth

Delhi’s drainage plan is almost 50 years old:

Oops, businesses are slowing down:

https://www.business-standard.com/budget/news/top-firms-profit-drop-led-to-cut-in-corporate-tax-estimates-revenue-secy-124072401088_1.html

Placement? Surely you’re joking:

https://news.careers360.com/niti-aayog-iti-study-placement-admission-students-teachers-vocational-education

It takes 10 minutes to work out those apprenticeship numbers - and we have an army of econ chieftains - Economic Advisers, PM's advisory council, Niti Ayog, Ministry of Industry, Ministry of Labour, Ministry of Education. Not one of them gave it those 10 minutes.

Viksit Bharat, my left digit.

Mohit Sir , this hullabaloo about LCTG etc is also overblown . Read a post from a fund manager on LinkedIn that past data suggests that out of the whole country around 7-10 lakh filed any of LTCG or STCG in the previous financial year . It have still not been able to make sense of this though because the country has upwards of 7 crore demat accounts and to think <1% of them report profit seems too low a percentage .