The Optimistic Indian

AI Image generated on NightCafe

Indians are optimistic about their economic future. They are just not very happy about their current situation.

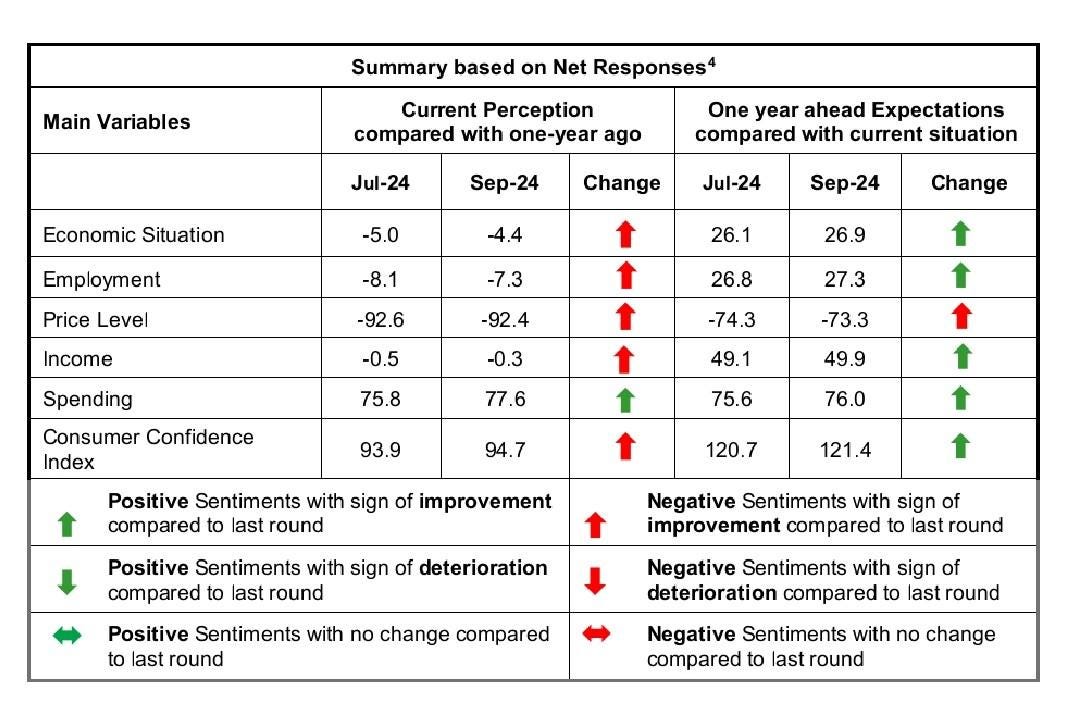

Every two months, our central bank, The Reserve Bank of India, asks Indian households to assess their economic situation*. Right now, they have a negative view on five out of the six measures surveyed: employment, income, prices, consumer confidence, and the catchall phrase, economic situation. On all counts, they are slightly less pessimistic than they were at the time of the last survey, in June, but the tables are largely marked in red:

In sharp contrast, households expect that things will be much better a year from now. The majority of households believe employment is worse than it was a year ago, but a large majority expect it to be better a year from now. The Consumer Confidence Index has still not recovered to pre-demonetisation levels of 100, but households expect it to surge to 121 a year from now.

Our households are most negative about price levels, the nay-sayers exceeding the positive folks by 92%. Projecting a year out, the balance shifts, to ‘only’ 73% negative.

The only marker on which most households report the outcome to be higher than a year ago is spending. I hesitate to call this a better outcome, because inflation can force citizens to spend more money without improving consumption, and even in the absence of an increase in incomes. And since they believe that employment, incomes and the overall economic situation are likely to improve, it is entirely logical to bridge the gap between the current reality and future expectations by saving less, or borrowing more.

Which is exactly what Indian households have been doing. Households are saving less, and borrowing more, which shows up, both in RBI’s regular data on household savings, as well as in NABARD’s September survey* of Rural Economic Conditions and Sentiments. There has been a lot of browbeating about the hazards of debt, about financing consumption expenditure with expensive short-term borrowing. The RBI has amplified the concerns by tightening the screws on lending by micro-finance organisations.

Increased household borrowing is not necessarily alarming. At 15% of GDP, Indian household debt is a quarter of the US level, of 60%. It is true that interest rates in India are higher, so the effective burden is higher, but I think the main issue is economic growth. If a family borrows in the hope of a better tomorrow, and its income levels do go up, taking a loan will have turned out to be a good thing. Conversely, if the young adults of the family don’t find jobs, or an older bread earner is laid off, debt - especially informal debt, at high interest rates - can cripple a family.

Which is why generating employment is key to the welfare of our Indian households. The majority of Indian households believe things will be better a year from now. If you track the household consumer confidence surveys for several years, as I have done, you can’t help but believe that their optimism in the future has been largely misplaced. In March of this year, 60% of Indian households believed that the employment situation a year from now would be better, even though the sentiment about the previous year was, on balance, neutral. Three surveys and six months later, nudged by reality, the perception of the current situation has turned negative. The future, too, has dimmed.

I wish this were not so. I wish there was a clear path to a growth in employment opportunities for Indian households. But I just don’t see it. And if you take the time to read the book I cover below, you will get an insight into how precarious and wretched life is for the majority of Indian households.

RBI consumer confidence survey, Sep 2024 https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Publications/PDFs/CCSSEP2024BE5BDEDE4D6C4548B3019E008F801D5A.PDF

National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development

Rural Economic Conditions and Sentiments Survey, Sep 2024

https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/tender/pub_0910240202031157.pdf

Many Lives of Syeda X

A reporter of deep integrity and empathy, Neha Dixit tells the story of Syeda X in this book just released by Juggernaut. In the passages below, I will try to give you the essence of the book in Neha’s words, but without the artefacts of quote-marks and connecting ellipses. In so doing, I hope that I don’t do injustice to the work, but prompt you to read it in its entirety.

She moved to Delhi from Banaras in 1995 with her husband and three children in the aftermath of riots triggered by the demolition of the Babri mosque. In Delhi, she moved from Chandni Chowk to Sabhapur to Karawal Nagar. She settled into the life of a poor migrant, juggling multiple jobs a day - from trimming the loose threads of jeans to cooking namkeen, and from shelling almonds to making tea strainers, doorknobs, pressure cookers, and photo frames.

Various Supreme Court orders on polluting industries forced her to move further and further away from the centre to the margins of the city. She has had over fifty jobs in almost thirty years, earning paltry wages in the process. And if she ever took time off, to nurse an illness or to attend to her children, her job would be lost to another faceless migrant fighting to take her place.

Almost 82 percent of working women in India are concentrated in the informal sector. After agricultural work, home-based work is the largest working sector for women. Yet, they are not considered workers by the state or the conventional male-dominated trade unions. The money they make is so abysmal that despite working twelve to sixteen hours a day, according to estimates, their monthly income is one-fifth of the legal minimum wage in Delhi. It just did not make sense to call themselves ‘workers’. This is in spite of the fact that many of the women I met with were the primary breadwinners of their families.This was true of Syeda. Her husband, Akmal, once a gifted weaver, struggled with alcoholism and ennui, and one of her two sons, Salman, died after the dome of a mosque collapsed on him. The other, Shazeb, fled to Himachal when his friendship with a Gujjar girl invited the wrath of the community. When demonetisation knocked the bottom out of the informal sector, and workers were left without work, Syeda’s daughter, Reshma, kept the family afloat. Thanks to a Delhi government scholarship, she had a bank account. Informal businessmen, with currency that became illegal overnight, paid Reshma for the use of her bank account, to bypass the limits on currency they could deposit in their own accounts.

One section of the book is about Reshma’s work in a mall in North Delhi, of the mall as a symbol of all that is desirable in modern India - air-conditioning, consumerism, clean bathrooms. The mall is also about the new lines that are drawn around access, about who gets to go in the front door, and who the back; about the insecurity and ugliness of those who believe they have made it to the other side.

The book ends with the destruction of the East Delhi riots, and the Covid lockdown that followed. Unlike millions of others who fled the cities for their villages, Syeda’s family had no place to call home:

Syeda went to her barsati, still full of soot, debris and haunting memories. She could still smell the ash in the air. For a few seconds, she was overcome by deja vu: was she in Banaras looking at their burned-down loom or in Karawal Nagar? The similarities were nauseating. The house was in utter disarray. Her TV was broken, as were the second-hand washing machine and fridge, and her trunk, which she called her CV, had been vandalized. The other trunk that had her jewellery - one pair of gold plated earrings, two pairs of silver anklets and Rs. 20,000 that she had collected to pay the bribe for Reshma’s job - were obviously missing. The bed was badly damaged, and the mattress had been set ablaze. The mob had blasted the LPG cylinder, as in all houses. Someone had even broken and twisted the blades of the fan.

Thanks, Ashish.

I have heard a similar comment from many readers.

If my little piece inspires you to read the book - and to share it with your daughters - then I have done a good deed!!

Mohit

It's hard to look at such dire facts and NOT get moved, get disturbed from my fake Stoic stance. My life is luxury and an average Indian is a lot worse in ways I cannot even imagine. I often struggle to get back to being serene and maintain jovial nature.

I plan to read the book and perhaps read these passages to my teen-age daughters, for them to be aware of realities of our cocoon...

Thanks!